The Rise of AI Coding Agents: Impact on Platform Engineering Teams

How AI coding agents like GitHub Copilot Workspace and Cursor are reshaping platform engineering. What teams need to prepare for and how to leverage these tools.

I used to think auth was a box you tick.

You wire up a login page, slap a JWT on the response, add a middleware, ship. And then you “do permissions later”.

And then reality hits: auth isn’t one thing. It’s three things (AAA), plus product decisions, plus infrastructure decisions, plus “how do I not accidentally let user A read user B’s data”.

This is a post about auth chaos: why building an app with security, authentication, and permissions is harder than it looks—especially when you mix modern identity providers (Entra/Okta/Auth0/etc.), self-managed tokens, and a permission model that will evolve.

Here’s the kind of bug that makes you stare at the wall.

/signin endpoint generates its own JWT with a local secret.So you can sign in successfully… and then your own API rejects the token.

Even worse: different parts of the backend might validate tokens differently:

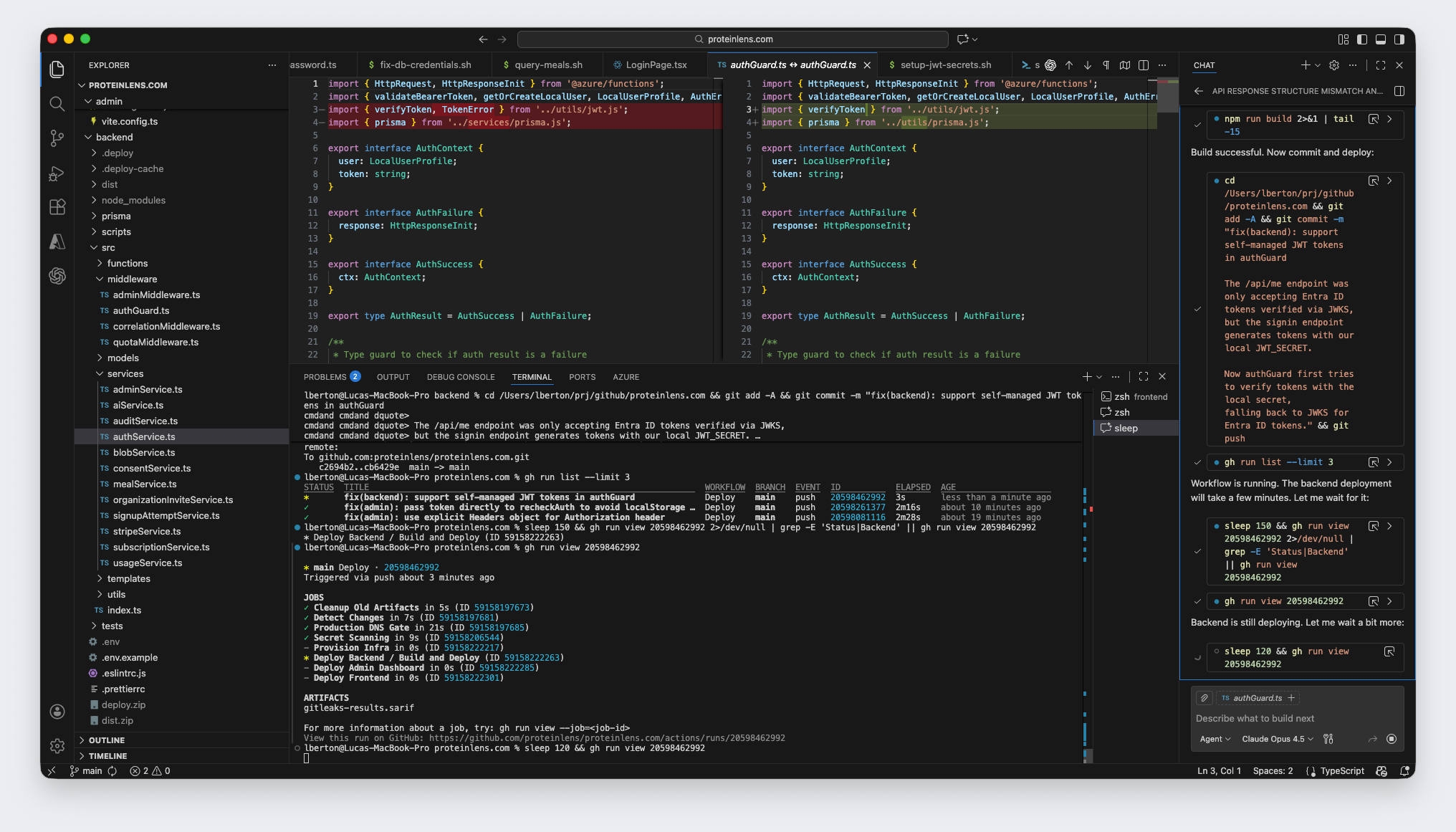

auth.ts uses verifyAccessToken() (local secret) ✅authGuard.ts uses validateBearerToken() (JWKS / Entra) ✅ (but incompatible with local tokens)Result: random endpoints work, others fail, and debugging feels like chasing ghosts.

This is auth chaos in one screenshot: your system doesn’t have a single “token contract.” It has two.

Because identity is a stack of choices, and it’s easy to accidentally make two incompatible sets of choices:

AAA is old terminology, but it’s still the best mental model for why “auth” expands.

This is where “it worked in dev” goes to die.

The part everyone ignores until:

This means:

If you’re building a real product, you will eventually need all three. The only question is when, and how painful you make the migration.

RBAC sounds like the solution because it’s easy to explain:

It’s a great MVP model… until you add scope.

Because authorization is rarely just “can user delete”. It’s:

can user delete this document in this workspace owned by this org while subscription is active?

RBAC alone doesn’t capture that. You need RBAC plus scoping.

If you want RBAC that scales, start with three explicit concepts:

Then make authorization checks look like:

Even if internally you still store roles as strings, force your code to think in these terms early.

Most permission systems fail because they were built backward:

This is why permissioning feels like quicksand: it’s coupled to product reality.

A good permission model reflects:

Your backend needs one crisp answer to these questions:

Who issues tokens?

What token types are accepted at the API boundary?

How does verification work?

What happens on rotation and revocation?

How do permissions flow into the request context?

Your suggested fix is pragmatic:

Update

authGuard.tsto try self-managed JWT verification first, then fall back to Entra JWKS verification.

That can work. But it’s also a warning sign: you now support two issuers and two trust models.

If you do this, make it explicit and safe:

iss (issuer) and aud (audience)A safer pattern is:

// Pseudocode: route by issuer, don't "guess"

const { iss } = decodeWithoutVerifying(token);

if (iss === "https://login.microsoftonline.com/<tenant>/v2.0") {

return verifyViaJwks(token);

}

if (iss === "your-app") {

return verifyViaLocalKey(token);

}

throw new Unauthorized("Unknown token issuer");If you must support both during a migration, do it like a migration:

Once you add RBAC, a bunch of non-obvious issues appear:

If you embed roles in JWT claims, and a user gets demoted, their token might keep admin powers until it expires.

Solutions:

The #1 authorization bug in SaaS is forgetting scope:

admin… of which org?Your DB queries must always include tenant scope. Every time. No exceptions.

When permissions change, you need to answer:

This becomes urgent the first time something “weird” happens.

If you’re building a product that might become B2B later, here’s the sane path:

Pick one auth model at the API boundary:

Keep identity in your DB (user record), even if IdP is used

Implement RBAC with scope (org/workspace)

Add basic audit logs for admin actions

Authentication chaos happens when you treat identity like an implementation detail.

But in a real app:

So yes: building an app with security, authentication, and permissions is difficult—not because the libraries are hard, but because the decisions are coupled and the failure modes are subtle.

If you want to avoid chaos, don’t aim for “auth done.” Aim for:

AI & Cloud Advisor with 18+ years experience. Author of 8 technical books, creator of Ansible Pilot, and instructor at CopyPasteLearn Academy. Speaker at KubeCon EU & Red Hat Summit 2026.

How AI coding agents like GitHub Copilot Workspace and Cursor are reshaping platform engineering. What teams need to prepare for and how to leverage these tools.

Backstage is the de facto IDP. Adding AI makes it transformative — auto-generated docs, intelligent search, and self-service infrastructure. Here's the architecture.

Schedule Kubernetes workloads when and where the grid is greenest. How carbon-aware scheduling works, the tools available, and the business case for sustainable compute.